Learn about one of the most extraordinary books at Blickling

Amongst the collection of books at Blickling, one in particular has a fascinating connection to the New England of the Puritans.

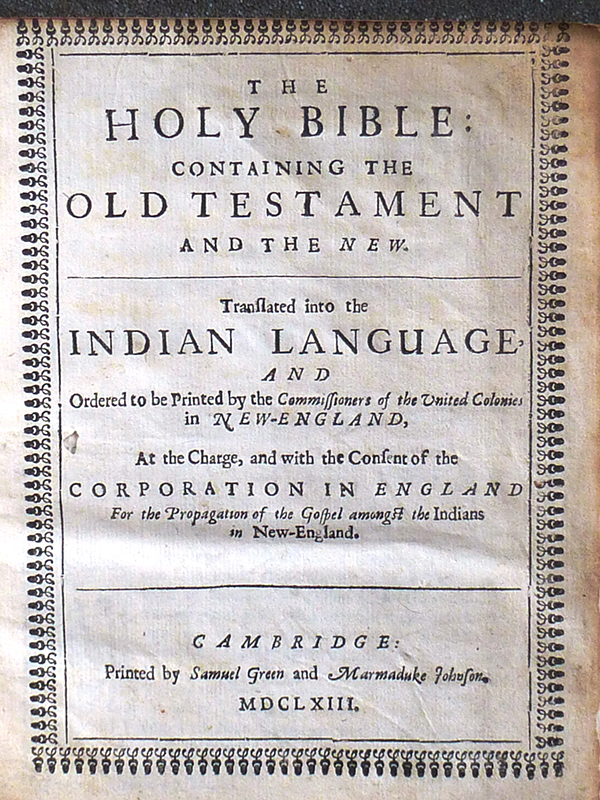

The book is commonly known as the “Eliot Indian Bible,” and was the first bible published in the American colonies. However, it was not printed in English; it was printed in Algonquin. This copy was first owned by the Puritan minister, John Higginson, whose children would find themselves on opposite sides of the infamous Salem Witch Trials: one a magistrate, the other a defendant.

Learn more about how this bible came to be and how this copy found its way back to England and ultimately into the collection at Blickling.

Read the article below published by the National Trust in the May 2013 edition of Arts, Buildings, Collections Bulletin

Photo by Blickling librarian, John Gandy.

Learn How You Can Help

Secure the Future of Books Like These

Published in Arts, Buildings, Collections Bulletin

There and Back Again

Investigating an early American book at Blickling Hall

By Nicola Thwaite, Assistant Libraries Curator (North)

A Norfolk country house may seem an unlikely place to find links to 17th-century European settlers in America. But one Blickling bible holds evidence of their continuing relationships with family in England, and a reminder that despite the hardships of contemporary sea travel, early emigrants to New England were not destined to remain there.

The Puritan John Eliot (1604-90)1 sailed to America in 1631 and spent more than 40 years as a missionary in eastern Massachusetts, preaching in the local Algonquin dialect. He also led a campaign which resulted in an ordinance from Parliament ‘for the advancement of civilization and Christianity among the Indians’ in July 1649 and the foundation of the first Protestant missionary society —now known as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG)—to raise funds for local ‘Commissioners for Indian Affairs’.

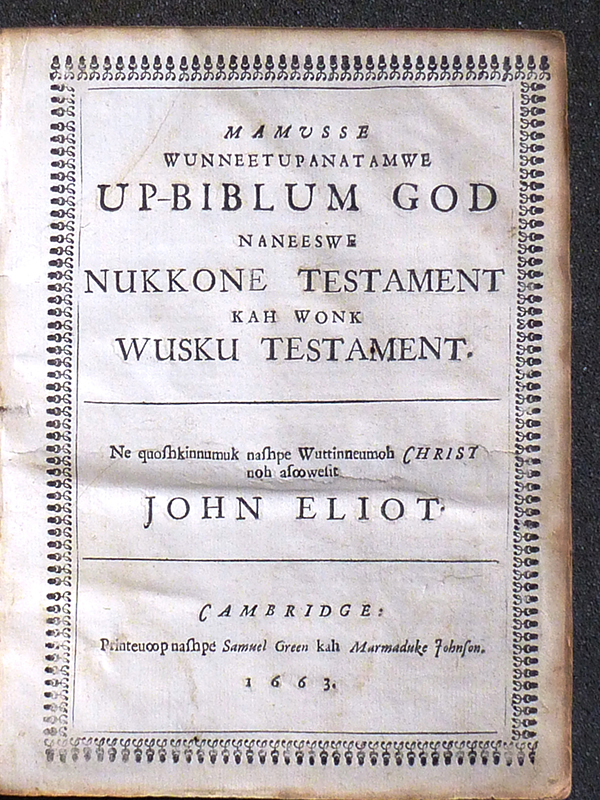

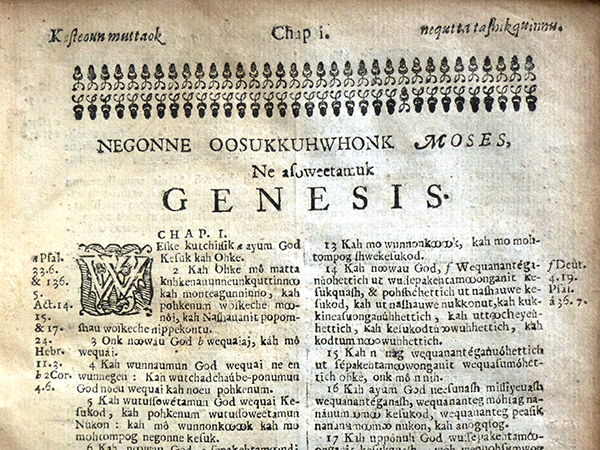

With the help of a native speaker, John Sassamon, Eliot spent ten years translating the bible into Massachusett Algonquin. The SPG agreed to support its publication and sent out a press, type fonts and a printer, Marmaduke Johnson, to assist the local Cambridge printer Samuel Green. The New Testament appeared in 1661 and the Old Testament and metrical psalms in 1663. This was the earliest example of the translation and printing of the complete bible in a new language for evangelical work, and the first bible in any language printed in North America; no English-language bible was printed there until the second half of the 18th century.

Photo by Blickling librarian, John Gandy.

Around 1,000 copies of the ‘Eliot Indian Bible’ were printed, of which at least 20 were sent immediately to England; these generally have an additional English title page and dedication to Charles II. Many of the surviving copies have inscriptions to Eliot’s friends and supporters: the publication was perhaps intended as much to attract funding as to enlighten the new converts.

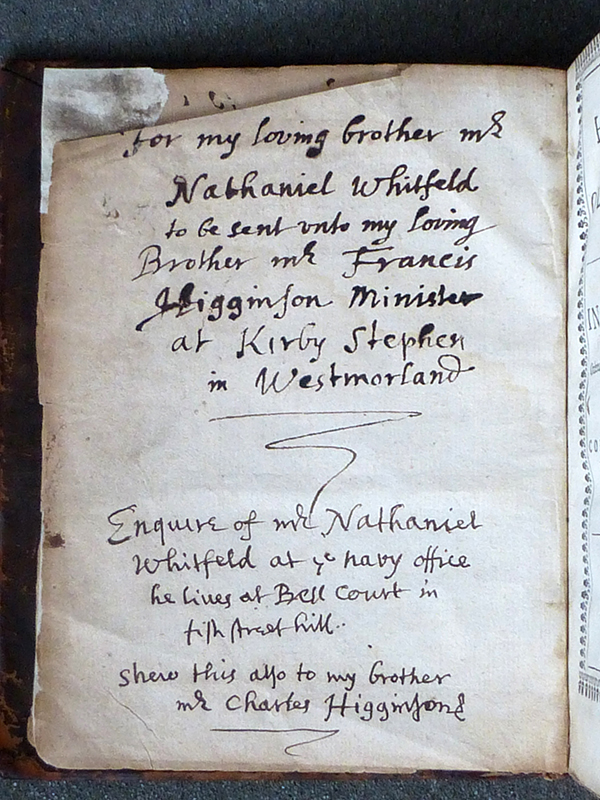

A contemporary inscription on the endpapers of the Blickling bible indicates that this was probably one of those sent straight to England:

‘For my loving brother Mr Nathaniel Whitfeld to be sent unto my loving Brother Mr Francis Higginson Minister at Kirby Stephen in Westmorland. Enquire of Mr Nathaniel Whitfeld at ye navy office he lives at Bell Court in fish street hill. Shew this also to my brother Mr Charles Higginson’.

Photo by Blickling librarian, John Gandy.

The anonymous sender can be identified as John Higginson (1616-1708), minister of Salem. John was the eldest son of the Leicestershire clergyman Francis Higginson (1586?-1630), who was appointed minister by the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1629. The family emigrated that summer and Francis became assistant minister to Salem Church, where he devised the ‘Salem Covenant’ still in use today. He also wrote a popular account of the colony, New-Englands Plantation, which immediately went through three editions, but he died of a fever in August 1630.

John Higginson also trained for the ministry and worked as a school-master in Guilford, Connecticut. In 1641 he married Sarah, daughter of Henry Whitfeld or Whitfield (1590/91-1657), whose home—the oldest stone house in New England —is now the Henry Whitfield State Museum. Whitfield had resigned his living at Ockley, Surrey, in 1638 and emigrated with several families from his parish. A man of means, he purchased land for the township of Menumkatuck (renamed Guilford) and served as unpaid minister for 11 years. The advent of the Common-wealth brought the prospect of reli¬gious change at home, and Whitfield returned to England in 1650, settling at Winchester. But he maintained his connections with and interest in New England: he became a member of the SPG and wrote a pamphlet The Light Appearing More and More Towards the Perfect Day to publicise the work of Eliot and his fellow missionary Thomas Mayhew.

John Higginson succeeded his father-in-law as minister at Guilford, where he also learnt to preach in the local language. In 1659 he too set off for England, but a storm drove his ship into Salem harbour and he accepted the post of pastor there, which he held until his death in 1708. It is unsurprising to find that his family were later involved in the Salem witch trials: his son John (b. 1646) was a magistrate, while his daughter, Ann Dolliver, was put on trial in 1692 but eventually freed.2

Photo by Blickling librarian, John Gandy.

John’s younger brother, Francis (1618-1673)—the intended recipient of the bible—taught in Cambridge, then returned to Europe in 1639 to study at Leiden. There were hopes that he would return to teach at Harvard, but instead Francis chose the English church. He was appointed rector at Kirkby Stephen, Westmorland in 1648 and remained there until his death, although he was suspended from his living for a short time for refusing to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity.3 Francis was an active opponent of local Quakers and wrote a 1653 pamphlet decrying their ‘irreligion’. Despite their physical separation, links between the family clearly remained strong: John’s son, another Francis (1660-1684?), returned to England to live with his uncle and was schooled at nearby Sedbergh before going to Cambridge.4

John Higginson directed the bible to Francis through his brother-in-law Nathaniel Whitfield (1629-1696) in London. Nathaniel emigrated with his parents in 1639 and it is not clear when he returned to England, although it was before 1657 when he witnessed Henry’s will in Winchester. There is no record of him returning with his father in 1650, but Henry was accompanied by Nathaniel’s sister, Dorothy (1619-1654) and her husband Samuel Desborough (1619-1690), who became parliamentary commissioner in Scotland.

From 1663-1692 Nathaniel was a clerk in the Navy Office. As a contemporary of Samuel Pepys, he receives three brief mentions in the diary, the first of which describes a moonlight boat trip to inspect docked ships (12 July 1663). Given his family’s religious and political background, this work was probably not without difficulty for Nathaniel: on 25 June 1665 Pepys is troubled on hearing of an attempt to make Whitfield ‘incapable of serving the King’. But he clearly survived this, and was appointed Chief Clerk in 1674.

Nathaniel’s address, Fish Street Hill, is now the site of the monument to the Great Fire, which started in the next street on 2 September 1666. He was apparently still living there that June, when a marriage licence was issued for Nathaniel Whitfeld, New Fish Street, and Sara Biggs of Portsmouth.5 Pepys mentions that Fish Street was destroyed, but the bible was presumably passed to Francis well before the conflagration!

Charles Higginson (1628-1677?), the third brother in John’s inscription, was a sailor who had lived in New Haven, Connecticut until at least 1649 but was now in Stepney and described as in the Jamaica trade. Charles had no apparent naval connection, but two elder brothers, Timothy (d.1653) and Samuel (d.1664), commanded state ships during the Commonwealth; all three died at sea.

Another endpaper contains the inscription: ‘Daniel Whitfeld March 20th 65’. More research is needed to identify Daniel, who seems not to be a direct relative of Henry Whitfield. The answer may lie in Cumbria: parish records show there were Whitfields—probably unrelated to the settlers—living near Kirkby Stephen in the 1660s, so Francis Higginson may simply have passed the book to a parishioner. I would be interested to hear from any Whitfield family historians who can offer a likely identification.

“Ellys was a keen biblical scholar who owned over 40 bibles in numerous

versions and languages, as well as many critical texts and commentaries.”

This Eliot Bible eventually passed into the library of Sir Richard Ellys (1682-1742) of Nocton, Lincolnshire. Ellys was a keen biblical scholar who owned over 40 bibles in numerous versions and languages, as well as many critical texts and commentaries. We do not yet know how he acquired the book, although a surviving collection of annotated sale catalogues6 could hold the answer. But it may have been a gift: Ellys was a firm Calvinist—he was a leading member of the nonconformist Princes Street congregation—and is thought to have had strong links with American settlers through his friends in London’s dissenting congregations.

Ellys’s links with New England were certainly strong enough to make his name known there: it seems that Harvard University was keen to acquire his collection to supplement its young library, and the Blickling collection still contains a presentation copy to Ellys of Harvard’s first library catalogue7, presumably sent as an encouragement to donate funds or books. Attempts were also made to acquire the library for English dissenting institutions, but when Ellys died, this important library was inherited by the Hobart family and came to Blickling.8

References

- See J. Frederick Fausz, ‘Eliot, John (1604-1690)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. ODNB also contains articles on Francis Higginson the elder, Henry Whitfield and Richard Ellys.

- See the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription project http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/salem/home.html

- Nightingale, The Ejected of 1662 in Cumberland & Westmorland, Manchester University Press, 1911, pp.1075-1089

- W. Higginson, Descendants of the Rev. Francis Higginson … Privately printed, 1910

- Allegations for Marriage Licences issued by … the Archbishop of Canterbury, Harleian Society publications, v.23, 1886, p.118

- See Mark Purcell’s article in ABC, August 2012, p.13

- Catalogus librorum Bibliothecae Collegij Harvardini quod est Cantabrigiae in Nova Anglia, Bartholomew Green, 1723, supplements to 1735.

- For more on Ellys’s library see G. Mandelbrote & Y. Lewis, Learning to Collect: the Library of Sir Richard Ellys at Blickling Hall, National Trust, 2004