Oxford University and the National Trust are working together to create experiences which teach, move and inspire. Oxford University historian and Royal Oak Lecturer Dr. Oliver Cox recently introduced this partnership and we’re proud to share his colleauge’s research on AngloFiles magazine.

By Dr. Sandra Mayer

On the wooded footpath gently meandering towards Hughenden Manor, the National Trust-owned country house near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, visitors are greeted by a large banner welcoming them to the former home of Benjamin Disraeli, “the most unlikely Victorian Prime Minister”. A best-selling novelist, flamboyant Byronic dandy, outstanding wit, Jewish-born social and ethnic outsider, eminent statesman and icon of Conservative politics, Disraeli (1804-1881) was indeed an anomaly in Victorian public life and politics – a mysterious nineteenth-century “Aladdin”, a “visitor from other ages, other climes, and another race, condescending to vary the dull monotony of politics”, as the Times referred to him in its obituary in 1881. Contemporaries never ceased to be puzzled by the uniqueness of his career against all odds and expectations: unaided by the usual prerequisites of personal wealth and elite education, Disraeli managed to scramble his way up to what he described as the “top of the greasy pole” as Queen Victoria’s favourite, two-times, Conservative Prime Minster.

Disraeli’s multi-faceted public persona made him an inscrutable enigma, frequently depicted in Victorian political cartoons as an impenetrable sphinx, but it also made him a celebrity. In our multi-media world, the term ‘celebrity’ evokes glamorous red-carpet displays and glossy magazine home stories; the short-lived (and, as we often think, undeserved) hype surrounding reality TV and casting show contestants; trivial tabloid journalism and the sordid business of phone hacking scandals; the hysteria of selfie-hunting fans; or, very generally, the pervasiveness of consumer culture and the commercialisation of a famous ‘brand name’. However, celebrity is far from an exclusively contemporary phenomenon, and many of the conditions that have helped shape modern celebrity culture – a flourishing print and commodity culture, technologies facilitating image reproduction, and a literate mass audience – have firmly been in place since the late eighteenth century. Following his first spell in office as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Disraeli had undoubtedly achieved celebrity status; his image circulated through illustrated newspapers, caricatures, and even material objects of commemoration, such as a waxwork display at Madame Tussaud’s – “that British Valhalla in which it is difficult for a civilian to gain a niche without being hanged”, as the Edinburgh Review archly remarked in its 1853 character sketch of Disraeli. His steep rise to power as leader of the Conservative Party and Prime Minister (1868; 1874-1880) made him one of the most famous politicians of his day, but it was not the gravitas of high government office alone that accounted for his unique pre-eminence in Victorian public life.

In the course of my work on the ‘Disraeli phenomenon’ against the background of nineteenth-century celebrity culture, it has become clear that Disraeli’s mysterious celebrity appeal resulted from the strange mingling of his many public roles and personae, which challenged contemporary norms of categorisation. As an 1881 commemorative verse tribute dedicated to Disraeli puts it, his parallel lives of “Sage, patriot, warrior, statesman, writer, friend, / Peer, Viscount, all harmoniously blend”, dynamically intersecting and colluding in the shaping of his public pre-eminence. A closer look at the individual components of Disraeli’s multi-faceted celebrity, therefore, is crucial to understanding his impact on the popular imagination during his lifetime and beyond, and it seems only fitting that “Disraeli the Celebrity” is currently the subject of a small exhibition put together by the curators at Hughenden.

The exhibition is part of a new series of themed temporary displays that cast a spotlight on a specific aspect of Disraeli’s life and career, encouraging visitors to have their say in the choice of upcoming exhibition themes.

The current exhibition is built around five objects from Hughenden’s remarkable collections that are considered representative of one particular facet of Disraeli’s fame. It is accompanied by a short video clip containing interesting footage, which cannot, however, make up for the conspicuous lack of object descriptions, rendering it difficult to check dates or fully take in important details. The first object – a copy of Disraeli’s last published novel, Endymion (1880), presented to him by his publisher – relates to Disraeli’s literary celebrity. To this day, Disraeli remains the only British Prime Minister who both started off and – to the confusion of his contemporaries – ended his career as a best-selling novelist. His high public profile as an eminent statesman only increased the public interest in his literary work, and for the copyright of Endymion, written and published in the wake of his second term in office as Prime Minister, he received a staggering advance payment of £ 10,000 (ca. $ 750,000 in today’s money) by his publisher Thomas Longman, who believed it to be “the largest sum ever paid for a work of fiction”. Disraeli’s novels may have provoked parodies and politically prejudiced reviews, but (or because of that) they immediately reached soaring sales figures and clearly resonated within Victorian popular culture. His 1870 novel Lothair, for example, triggered a veritable ‘Lothairmania’, with ships, streets, songs, guns and horses named after the book’s hero and heroine.

The current exhibition is built around five objects from Hughenden’s remarkable collections that are considered representative of one particular facet of Disraeli’s fame. It is accompanied by a short video clip containing interesting footage, which cannot, however, make up for the conspicuous lack of object descriptions, rendering it difficult to check dates or fully take in important details. The first object – a copy of Disraeli’s last published novel, Endymion (1880), presented to him by his publisher – relates to Disraeli’s literary celebrity. To this day, Disraeli remains the only British Prime Minister who both started off and – to the confusion of his contemporaries – ended his career as a best-selling novelist. His high public profile as an eminent statesman only increased the public interest in his literary work, and for the copyright of Endymion, written and published in the wake of his second term in office as Prime Minister, he received a staggering advance payment of £ 10,000 (ca. $ 750,000 in today’s money) by his publisher Thomas Longman, who believed it to be “the largest sum ever paid for a work of fiction”. Disraeli’s novels may have provoked parodies and politically prejudiced reviews, but (or because of that) they immediately reached soaring sales figures and clearly resonated within Victorian popular culture. His 1870 novel Lothair, for example, triggered a veritable ‘Lothairmania’, with ships, streets, songs, guns and horses named after the book’s hero and heroine.

The second object highlights the exotic appeal of Disraeli’s ‘otherness’, which, despite his Christian baptism at the age of 13, remained steadfastly linked to his Jewish origins. The seal stamp with the Sicilian Tower, a tribute to his Sephardic lineage, attests to his need to romanticise his Jewish heritage in stubborn defiance of the rampantly anti-Semitic prejudice he was confronted with all his life. Disraeli staunchly countered the threat of social and political marginalisation by embracing and glorifying his Jewishness as a key element in the fashioning of his self-image.

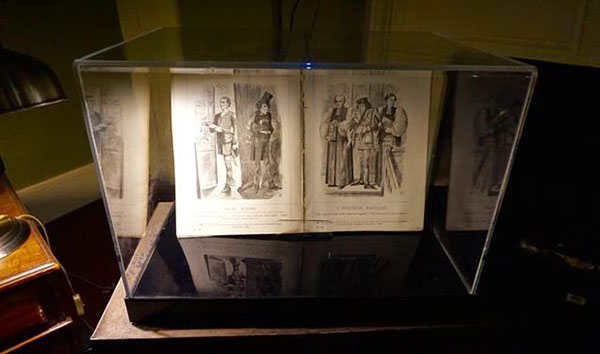

Disraeli’s transformation from assiduous social climber and silver-fork novelist to distinguished statesman coincided with the growth of political celebrity culture as a direct consequence of the gradual expansion of the electorate. The changing political culture of the 1860s and 1870s saw the proliferation of commercially produced visual and material representations of politicians, such as caricatures, commemorative plates or Staffordshire figurines. Political cartoons, in particular, were designed to appeal to a mass audience, successfully linking the spheres of politics, art and popular culture. The third object, a pair of cartoons from Punch, pays tribute to Disraeli’s fame as a politician. In the course of his career, he featured in over 280 of the periodical’s cartoons, which were highly influential in shaping and raising his public profile.

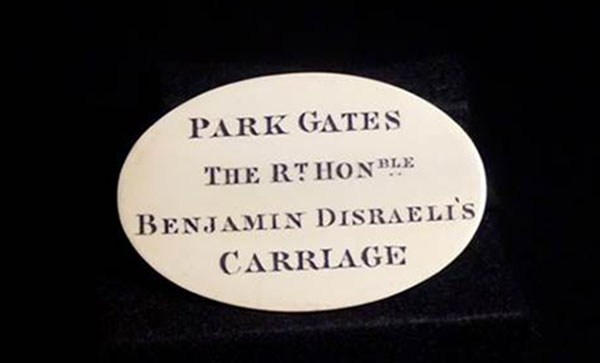

The exhibition also zooms in on the special relationship between Disraeli and Queen Victoria, represented by an ivory pass granting Disraeli’s carriage special admittance to Buckingham Palace through St James’s Gate. At first glance an odd pair, they shared a symbiotic relationship, with Disraeli dazzled by the glamour of high social rank and the widowed Queen desperate for a male friend and confidant who would value her political opinions. Keen to increase the symbolic significance of the Crown, Disraeli was the main force behind the Royal Titles Act of 1876 that made Queen Victoria Empress of India, who in turn created him Earl of Beaconsfield. Her presence at Hughenden – which she visited in 1877 – manifests itself in a number of royal portraits of herself and the Prince Consort, easily recognisable by the coronet adorning their frames and given to Disraeli as tokens of friendship. When Disraeli died in 1881, the Queen not only sent a wreath of wild primroses, Disraeli’s favourite flowers, but came to visit his tomb and had a monument erected in his honour in Hughenden Church, bearing the inscription “Kings loveth him that speaketh right”.

Queen Victoria’s romantic parting gesture to her favourite premier sparked off a posthumous cult of memorialisation that would turn Disraeli into a national and political icon. The custom of wearing ‘Beaconsfield buttonholes’ to mark the anniversary of his death was soon institutionalised as ‘Primrose Day’, when his grave in the Hughenden churchyard became a site of pilgrimage, as revealed by some extraordinary Pathé film footage. These efforts of immortalising Disraeli led to the foundation of the Primrose League, a powerful organisation committed to upholding Conservative values which, at its height, had over one million members and was only disbanded in 2004. The exhibition’s final object, a Primrose League badge with the organisation’s motto “Empire and Liberty”, therefore hints at the fascinating story of Disraeli’s afterlives in the popular imagination.

Disraeli indeed lives on in films, video games, cartoons, fictional biographies and songs and continues to be (mis)quoted in political speeches across party lines. At Hughenden, where Disraeli enjoyed the tranquillity of country life away from the cares and demands of political office, the visitor gets a sense of Disraeli the private man, but the picture remains sketchy and incomplete until we pay attention to the dynamics involved in the formation of his public image. A closer look at “Disraeli the Celebrity” helps us crack the riddle of the Disraelian Sphinx, and it would be welcome to see this temporary display turned into a larger exhibition that builds on the fruitful collaboration between Hughenden curators and academics set up by The Thames Valley Country House Partnership. This knowledge exchange initiative, supported by the University of Oxford, aims at creating sustainable partnerships between the heritage and higher education sectors. In the context of my own work on Disraeli as a Victorian celebrity at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, it was certainly instrumental in forging a mutually enriching and beneficial collaboration that will no doubt be continued in the future.

Links and further information:

- Sandra Mayer. “Pegasus and Carthorse: The Many Shades of Disraeli’s Celebrity.” University of Oxford Podcast. 8 July 2015.

- Oliver Cox and Robert Bandy. “Working with Hughenden Manor: Solving the Statesman’s Rooms.” University of Oxford Podcast. 8 July 2015.

- Thames Valley Country House Partnership

Sandra Mayer is a Lecturer in English Literature and Culture at the University of Vienna and a Visiting Scholar at the University of Oxford’s English Faculty and Wolfson College. She is currently working on a monograph that focuses on the intersections of authorship, literary celebrity and politics in nineteenth-century Britain.